Viral Political Ads May Not Be As Persuasive As You Think

In a partnership with the digital media strategists at Harmony Labs, Swayable tested to see if engagement on social media was related to content persuasiveness.

From Wired:

When a political ad goes viral on Facebook, conventional wisdom holds that it was a success. After all, the Golden Rule of advertising in the digital age is simple: Engagement is good. It’s good for Facebook too. The more time users spend watching, commenting, clicking, and sharing on its platform, the more money the company makes. Little wonder, then, that Facebook allows advertisers to test which ads get the most engagement with a single click.

That model works just fine when you’re trying to get people to donate or volunteer for a cause. It’s easy enough to see whether all those impressions translate into more donations and sign-ups. These types of ads are known as direct-response ads, because they urge the target to take some action.

The calculus changes when it comes to persuasion ads, which aim to build support for a certain candidate or issue among people who haven't made up their minds yet. The key to persuasion is not simply engaging the biggest audience but successfully moving the right one. Still, lots of political advertisers, including campaigns and advocacy groups, use engagement as a proxy for persuasion. That's particularly true when they don't have the means for more in-depth poll testing. Sometimes we in the press also conflate the two, believing that virality and persuasiveness are somehow synonymous.

But is that true? Or, in the age of echo chambers and filter bubbles, is high engagement really just a sign that you’re preaching to the converted?

That's the question a group of progressive digital strategists working out of Harmony Labs, a nonprofit dedicated to studying media influence, set out to answer in a series of recent tests.

“The thing the platforms are driving you to is increasing their revenue, but it doesn’t necessarily persuade the people that need to be persuaded,” says Nathaniel Lubin, former White House digital director under President Barack Obama. Lubin designed the experiments along with Peter Koechley, cofounder of UpWorthy, whose founding mission was to make viral content promoting political and social issues.

Through Harmony Labs, Lubin and Koechley recently launched a project geared toward sourcing and creating left-leaning advocacy content that’s both engaging and persuasive. They call it the Meme Factory.

Designing the Meme Factory study

For the Meme Factory project, Swayable sourced study participants, dividing them into groups that mirrored the audiences Lubin and Koechley targeted on Facebook. For each video, there was a control group and a test group.

The control groups were shown what Slezak calls “placebo content,” unrelated videos like a public service announcement about texting and driving. The test group watched one of the Meme Factory videos. Then both groups were given a survey asking how they agreed with the points highlighted in the video, and whether they’d take action on the issue.

If the test group agreed more than the control group (who saw only the placebo), then Swayable deemed them, well, swayed. All together, the experiment surveyed 10,000 people, amassing 100,000 data points about them in total, including basic information about demographics and partisan affiliation.

One of the most engaging DACA videos was called “Heartache,” a tearjerker of an ad that featured crying children being separated from their undocumented parents. It blamed “Donald Trump’s America” for their sorrow and asked viewers to share the video if they think America is better than this.

Far less engaging was “What Would You Do?”---a split-screen video of a woman watching another video about the DACA debate. It’s loaded with snark, pop culture references, and emojis.

In the end, the videos' success on Facebook, or lack thereof, turned out to have little impact on their ability to persuade.

Swayable found that after watching "Heartache," the people who identified as most conservative were less supportive of DACA than the control group. The "What Would You Do?" video, meanwhile, elicited more support for DACA among even the most conservative participants, compared to the control group.

But those are just two examples.

Persuasion vs. digital engagement

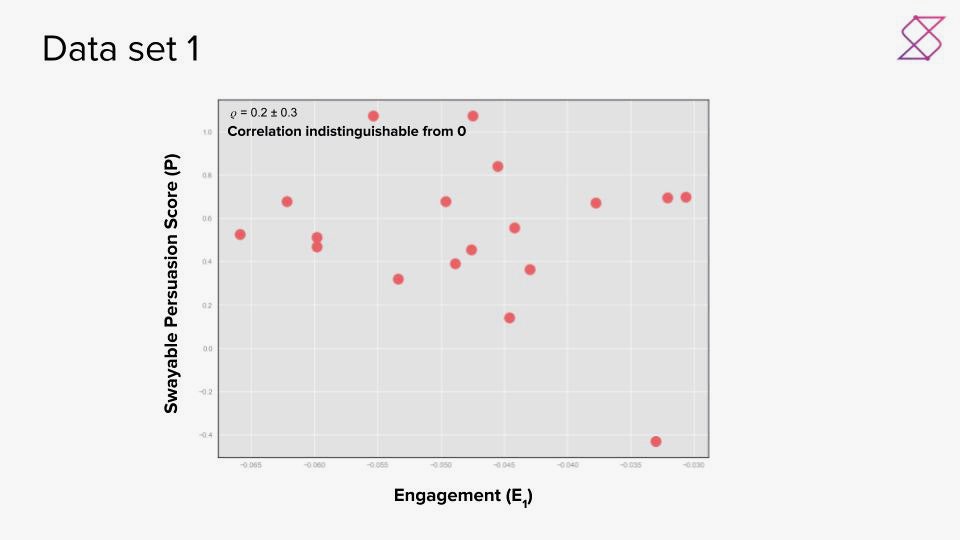

Swayable plotted the persuasion and engagement scores of dozens of combinations of videos and audiences, using 18 videos covering a range of progressive issues from immigration to tax reform.

All videos were promoted on Facebook and engagement metrics for clicks, likes, shares, and time spent were collected. Swayable used random controlled trial experiments to measure persuasiveness for each of the videos through Swayable’s platform. As before, participants were divided into control and test groups assigned to watch either one video ad or an irrelevant PSA video for the control group (the placebo). All respondents were then surveyed on whether they agreed with the video and if they’d take action.

The experiment surveyed 10,000 people in 24 hours and found no correlation between the opinion change and engagement metrics. If the two were correlated, these graphs would show a line. The haphazard dots prove there’s no correlation at all.

“There’s nothing but just random static,” Slezak says.

-4.jpg)

The Conclusion: Engagement metrics aren’t a viable proxy for whether content had its intended impact.

Interested in testing persuasion instead? Book a demo with Swayable to see how to quickly set up your own RCT test.